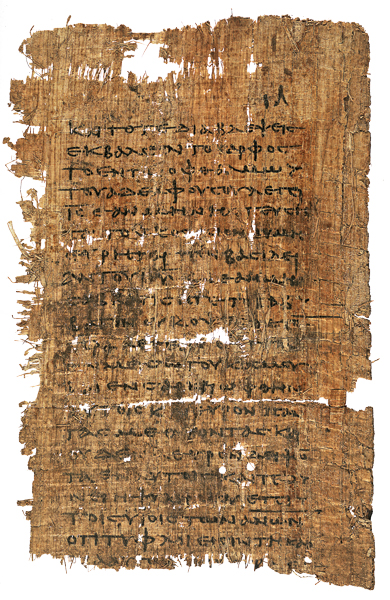

Why the Muratorian Fragment is a Big Deal and What You Need to Know About It3/13/2017 In order to diminish the importance and relevance of the Bible, it's common for skeptics to point out that the early Christians didn't even have an official Bible. They claim that what we now call the 'New Testament' wasn't compiled untilhundreds of years after the life of Christ and the Apostles, when church councils convened to decide which books were 'in' and which ones were 'out.' Famously, Dan Brown, in his best-selling book,The DaVinci Code, even alleged that the Emperor Constantine chose the books at the council of Nicaea in AD 325.(1) The Muratorian Fragmentis a big deal because its very existence is evidence that these notions are not true. What is the Muratorian Fragment? Sometimes called the 'Muratorian Canon,' the fragment is an ancient manuscript that includes a list of New Testament books. While the fragment itself dates from the 7th or 8th century, the list of biblical books it contains dates from around AD 180.(2) Other than a highly abridged collection by the heretic Marcion, it is the oldest list of New Testament books we have, and it affirms 22 out of the 27 books.This is remarkably early to have such a comprehensive canon. When speaking of the biblical canon, some scholars insist that the word canon can only be applied to the final, closed list of books that was officially sanctioned by the church in later centuries. However, many prominent scholars disagree. Dr. Michael Kruger writes, 'The term canoncan be employed as soon as a book is regarded as 'Scripture' by early Christian communities.'(3) The Muratorian Fragment shows us which books early Christians considered to be Scripture. What do you need to know about the Muratorian Fragment? 1. It affirms all four Gospels, the book of Acts, all 13 epistles of Paul, along with Jude, 1 John and 2 John, and Revelation. (There is also a possibility that 3rd John is included but that is disputed.) What this tells us: There was widespread agreement regardingmostof the books of the New Testament by the end of the 2nd century. 2. It mentions the non-canonical Apocalypse of Peter but testifies to the fact that not everyone was in agreement about its authority. What this tells us: There definitely was some disagreement over certain books, but it highlights the fact that there was general agreement overmostof them. 3. It references theShepherd of Hermasas a book that was widely read and appreciated among early Christians but was rejected as Scripture because it was written 'very recently in our times.' What this tells us:Early Christians understood the concept of canon and recognized certain attributes in canonical books by rejecting anything written after the time of the Twelve Apostles (the apostolic era). This means the canon was, in principle, already closed by the beginning of the 2nd century, when the Apostles were no longer alive. (4) Why is the Muratorian Fragment a big deal? Remember the claim that Constantine chose the books of the New Testament? Other than the fact that there is no historical evidence to support this assertion, the Muratorian Fragment existed before he was even born, and the official canon wasn't finalized until about 60 years after his death. Constantine is certainly an interesting historical figure, but he did not determine the canon. The Muratorian Fragment demonstrates that as early as the late 2nd century (not even 100 years after the last of the Apostles died), there was a core canon that was affirmed by Christians and accepted as Scripture on par with the Old Testament. And that is a very big deal! Please subscribe to have my weekly blog posts delivered directly to your inbox, and join the conversation on Facebook and Twitter! References: (1) Dan Brown, The DaVinci Code (Anchor, 2009) p. 251-252 (2) Andreas J. Kostenberger & Michael J. Kruger, The Heresy of Orthodoxy (Crossway, 2010) p. 157 (3)Michael J. Kruger, The Question of Canon: Challenging the Status Quo in the New Testament Debate (IVP Academic, 2013) p. 35 (4) Kostenberger & Kruger, p. 170-171 3/14/2017 12:49:57 am Dear Alisa, 3/14/2017 12:34:51 pm Hi Herman, 3/14/2017 02:12:57 pm Im a bit confused by the article. It states the fragment is from the 7th century but that its info is from the 2nd century? If the fragment is dated the 7th century wouldnt that make the list a 7th century list? Please elaborate. 3/14/2017 06:22:02 pm Hi Dalee. The Muratorian Fragment is a collection of theological works including treatises from early church fathers and early Christian creeds, so all of the works copied in it are from different time periods. One of the reasons scholars date the canon list to the late 2nd century is because it says that one of the books in the list, the Shepherd of Hermas, was written 'very recently, in our own times, in the city of Rome, while his brother, Pius, was occupying the bishop's chair of the church of the city of Rome.' So they know it was from that particular time period and could be dated no later than AD 200. A couple of scholars challenged the dating and tried to put it closer to the 4th century, but that has not been accepted by the vast majority of the scholarly community. The generally accepted date is AD 170-180. 3/19/2017 12:45:23 am Questioning the validity of Scripture seems to be a trend not only in secular circles but also in the church. The rising argument is that we must define things by 'what your heart says' because even Scripture has fallacies. In my search for the validity of Scripture, one of the harshest arguments against it was the canonical argument of the books of the New Testament. Thank you, Alisa. This has been great as usual and I will be looking into the books referenced. Stay strong in the Lord. 4/24/2017 04:20:19 pm Emily, 4/24/2017 09:51:32 pm Hi Barry, the Muratorian Fragment is a collection of different works from different time periods. The presence of the NT list within it, and it's date is what is significant regarding canon. It lets us know what the general consensus was. Regarding the other works in the fragment, they would have to be assessed theologically on their own merits. 4/25/2017 06:01:53 pm Correct..and the MF's testimony to how John's gospel contents came about, is in the same section mentioning the canonical NT books. So however early you date this list, you are dating the vision-explanation for John's gospel that early too. 4/25/2017 08:31:00 pm I didn't make a claim regarding the testimony about John's gospel, which is a different subject. Your comment is irrelevant to this post, which is about the dating of the canonical list within the MF, not the theological content of other works it contains. 4/27/2017 06:11:36 pm I disagree that my post was irrelevant, the MF's testimony to the origin of John follows immediately after John's gospel is named as the fourth gospel. When you assign a date to the canonical list, you are assigning a date to a story about the origin of John's gospel, that most of today's conservatives, such as yourself, do not believe represents the truth. Your comment will be posted after it is approved. Leave a Reply. |

22 of the 27 books of the New Testament were listed in what is called the Muratorian Fragment, dated from about 180 AD. This list includes everything but Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, and possibly 3 John, indicating that the bulk of the New Testament canon was established at an extraordinarily early date.

| Bible Research >Canon > Disputed NT Books |

The table below shows which of the disputed New Testament books and other writings are included in catalogs of canonical books up to the eighth century. Y indicates that the book is plainly listed as Holy Scripture;N indicates that the author lists it in a class of disputed books; M indicates that the list may be construed to include the book as Holy Scripture; X indicates that the book is expressly rejected by the author. An S indicates that the author does not mention the book at all, which implies its rejection. See notes on the authorities and books following.

KEY TO BOOKS

|

| 1. Greek & Latin | Date | Heb. | Jas. | Jn. | Pet. | Jude | Rev. | Shep. | Apoc. | Barn. | Clem. |

| Muratorian Fragment | 170 | S | S | M | S | Y | Y | X | N | S | S |

| Origen | 225 | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Eusebius of Caesarea | 324 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | X | X | X | S |

| Cyril of Jerusalem | 348 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S |

| Cheltenham list | 360 | S | S | Y | Y | S | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Council of Laodicea | 363 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S |

| Athanasius | 367 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | X | S | S | S |

| Gregory of Nazianzus | 380 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S |

| Amphilocius of Iconium | 380 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | S | S | S | S |

| Rufinus | 380 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | X | S | S | S |

| Epiphanius | 385 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Jerome | 390 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Augustine | 397 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| 3rd Council of Carthage | 397 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Codex Claromontanus | 400 | M | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Letter of Innocent I | 405 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | X | S | S |

| Decree of Gelasius | 550 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | X | S | S | S |

| Isadore of Seville | 625 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| John of Damascus | 730 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| 2. Syrian | Date | Heb. | Jas. | Jn. | Pet. | Jude | Rev. | Shep. | Apoc. | Barn. | Clem. |

| Apostolic Canons | 380 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | Y |

| Peshitta Version | 400 | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Report of Junilius | 550 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | S | S | S | S |

Log of making dataopenbve data publishing studio.

NOTES

The most satisfactory treatment in English of the Church's New Testament canon is Bruce Metzger's The Canon of the New Testament: its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987). Still useful is the earlier study by B.F. Westcott, A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament (London: MacMillan, 1855; 6th edition 1889; reprinted, Grand Rapids, 1980). For a popular conservative survey see Norman Geisler and William Nix, General Introduction to the Bible (Chicago: Moody Press, 1986).

- So the men reclined, about five thousand in number. F 11 Then Jesus took the loaves, gave thanks, and distributed them to those who were reclining, and also as much of the fish as they wanted. G 12 When they had had their fill, he said to his disciples, 'Gather the fragments left over, so that nothing will be wasted.' 13 So they collected.

- Fragments of the Greek scriptures were also found at Qumran (as a part of the Dead Sea Scrolls). It was the Greek Old Testament that the Apostles and early Christians used because it was in the language of the dispersion. As everyone knows, Vespasian and Titus conquered Jerusalem in 70 A.D., burned down Herod's Temple and exiled the Jewish.

Muratorian Fragment. The oldest known list of New Testament books, discovered by Muratori in a seventh century manuscript. The list itself is dated to about 170 because its author refers to the episcopate of Pius I of Rome (died 157) as recent. He mentions only two epistles of John, without describing them. The Apocalypse of Peter is mentioned as a book which 'some of us will not allow to be read in church.' See English text.

Origen. An influential teacher in Alexandria, the chief city of Egypt. His canon is known from the compilation made by Eusebius for his Church History (see below). He accepted Hebrews as Scripture while entertaining doubts about its author. See English text.

Eusebius of Caesarea. An early historian of the Church. His list was included in his Church History. He ascribed Hebrews to Paul. See English text.

Cyril of Jerusalem. Bishop of Jerusalem. The omission of Revelation from his list is due to a general reaction against this book in the east after excessive use was made of it by the Montanist cults. See English text.

Cheltenham list. A catalog dating from the middle of the fourth century contained in two medieval Latin manuscripts, probably from Africa. See Latin text with translation.

Council of Laodicea. The authenticity of this list of canonical books has been doubted by many scholars because it is absent from various manuscripts containing the decrees of the regional (Galatian) Council. The list may have been added later. On the omission of Revelation see Cyril of Jerusalem above. See English text.

Athanasius. Bishop of Alexandria. His list was published as part of his Easter Letter in 367. After the list he declares, 'these are the wells of salvation, so that he who thirsts may be satisfied with the sayings in these. Let no one add to these. Let nothing be taken away.' See English text.

Gregory of Nazianzus. Bishop of Constantinople from 378 to 382. On the omission of Revelation see Cyril of Jerusalem above. See English text.

Amphilocius of Iconium. Bishop of Iconium in Galatia. See English text.

Rufinus. An elder in the church in Aquileia (northeast Italy), and a friend of Jerome. The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Epiphanius. Bishop of Salamis (isle of Cyprus) from 367 to 402. The Greek text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Jerome. Born near Aquileia, lived in Rome for a time, and spent most of his later life as a monk in Syria and Palestine. He was the most learned churchman of his time, and was commissioned by the bishop of Rome to produce an authoritative Latin version (the Vulgate). The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Augustine. Bishop of Hippo (in the Roman colony on the northern coast of western Africa). The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

| Bible Research >Canon > Disputed NT Books |

The table below shows which of the disputed New Testament books and other writings are included in catalogs of canonical books up to the eighth century. Y indicates that the book is plainly listed as Holy Scripture;N indicates that the author lists it in a class of disputed books; M indicates that the list may be construed to include the book as Holy Scripture; X indicates that the book is expressly rejected by the author. An S indicates that the author does not mention the book at all, which implies its rejection. See notes on the authorities and books following.

KEY TO BOOKS

|

| 1. Greek & Latin | Date | Heb. | Jas. | Jn. | Pet. | Jude | Rev. | Shep. | Apoc. | Barn. | Clem. |

| Muratorian Fragment | 170 | S | S | M | S | Y | Y | X | N | S | S |

| Origen | 225 | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Eusebius of Caesarea | 324 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | X | X | X | S |

| Cyril of Jerusalem | 348 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S |

| Cheltenham list | 360 | S | S | Y | Y | S | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Council of Laodicea | 363 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S |

| Athanasius | 367 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | X | S | S | S |

| Gregory of Nazianzus | 380 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S |

| Amphilocius of Iconium | 380 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | S | S | S | S |

| Rufinus | 380 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | X | S | S | S |

| Epiphanius | 385 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Jerome | 390 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Augustine | 397 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| 3rd Council of Carthage | 397 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| Codex Claromontanus | 400 | M | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S |

| Letter of Innocent I | 405 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | X | S | S |

| Decree of Gelasius | 550 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | X | S | S | S |

| Isadore of Seville | 625 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| John of Damascus | 730 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S |

| 2. Syrian | Date | Heb. | Jas. | Jn. | Pet. | Jude | Rev. | Shep. | Apoc. | Barn. | Clem. |

| Apostolic Canons | 380 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | Y |

| Peshitta Version | 400 | Y | Y | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Report of Junilius | 550 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | S | S | S | S |

Log of making dataopenbve data publishing studio.

NOTES

The most satisfactory treatment in English of the Church's New Testament canon is Bruce Metzger's The Canon of the New Testament: its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987). Still useful is the earlier study by B.F. Westcott, A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament (London: MacMillan, 1855; 6th edition 1889; reprinted, Grand Rapids, 1980). For a popular conservative survey see Norman Geisler and William Nix, General Introduction to the Bible (Chicago: Moody Press, 1986).

- So the men reclined, about five thousand in number. F 11 Then Jesus took the loaves, gave thanks, and distributed them to those who were reclining, and also as much of the fish as they wanted. G 12 When they had had their fill, he said to his disciples, 'Gather the fragments left over, so that nothing will be wasted.' 13 So they collected.

- Fragments of the Greek scriptures were also found at Qumran (as a part of the Dead Sea Scrolls). It was the Greek Old Testament that the Apostles and early Christians used because it was in the language of the dispersion. As everyone knows, Vespasian and Titus conquered Jerusalem in 70 A.D., burned down Herod's Temple and exiled the Jewish.

Muratorian Fragment. The oldest known list of New Testament books, discovered by Muratori in a seventh century manuscript. The list itself is dated to about 170 because its author refers to the episcopate of Pius I of Rome (died 157) as recent. He mentions only two epistles of John, without describing them. The Apocalypse of Peter is mentioned as a book which 'some of us will not allow to be read in church.' See English text.

Origen. An influential teacher in Alexandria, the chief city of Egypt. His canon is known from the compilation made by Eusebius for his Church History (see below). He accepted Hebrews as Scripture while entertaining doubts about its author. See English text.

Eusebius of Caesarea. An early historian of the Church. His list was included in his Church History. He ascribed Hebrews to Paul. See English text.

Cyril of Jerusalem. Bishop of Jerusalem. The omission of Revelation from his list is due to a general reaction against this book in the east after excessive use was made of it by the Montanist cults. See English text.

Cheltenham list. A catalog dating from the middle of the fourth century contained in two medieval Latin manuscripts, probably from Africa. See Latin text with translation.

Council of Laodicea. The authenticity of this list of canonical books has been doubted by many scholars because it is absent from various manuscripts containing the decrees of the regional (Galatian) Council. The list may have been added later. On the omission of Revelation see Cyril of Jerusalem above. See English text.

Athanasius. Bishop of Alexandria. His list was published as part of his Easter Letter in 367. After the list he declares, 'these are the wells of salvation, so that he who thirsts may be satisfied with the sayings in these. Let no one add to these. Let nothing be taken away.' See English text.

Gregory of Nazianzus. Bishop of Constantinople from 378 to 382. On the omission of Revelation see Cyril of Jerusalem above. See English text.

Amphilocius of Iconium. Bishop of Iconium in Galatia. See English text.

Rufinus. An elder in the church in Aquileia (northeast Italy), and a friend of Jerome. The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Epiphanius. Bishop of Salamis (isle of Cyprus) from 367 to 402. The Greek text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Jerome. Born near Aquileia, lived in Rome for a time, and spent most of his later life as a monk in Syria and Palestine. He was the most learned churchman of his time, and was commissioned by the bishop of Rome to produce an authoritative Latin version (the Vulgate). The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Augustine. Bishop of Hippo (in the Roman colony on the northern coast of western Africa). The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Third Council of Carthage. Not a general council but a regional council of African bishops, much under the influence of Augustine. See English text.

Codex Claromontanus. A stichometric catalog from the third century is inserted between Philemon and Hebrews in this sixth century Greek-Latin manuscript of the epistles of Paul. The list does not have Hebrews, but neither does it have Philippians and 1 and 2 Thessalonians, and so many scholars have supposed that these four books dropped out by an error of transcription, the scribe's eye jumping from the end of the word ephesious (Ephesians) to the end of ebraious (Hebrews). Besides the books indicated on the table the list includes the apocryphal Acts of Paul. See English text.

Letter of Innocent I. A letter from the bishop of Rome to the bishop of Toulouse. The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Decree of Gelasius. Traditionally ascribed to Gelasius, bishop of Rome from 492 to 496, and thought to be promulgated by him as president of a council of 70 bishops in Rome, but now regarded by most scholars as spurious, and probably composed by an Italian churchman in the sixth century. The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Isadore of Seville. Archbishop of Seville (Spain), and founder of a school in that city. His list appears in an encyclopedia he compiled for his students. The Latin text is given in Westcott, appendix D.

John of Damascus. An eminent theologian of the Eastern Church, born in Damascus, but a monk in Jerusalem for most of his life. His list is derived from the writings of Epiphanius. The Greek text is given in Westcott, appendix D. See English text.

Apostolic Canons. One of many additions made by the final editor of an ancient Syrian book of church order called The Apostolic Constitutions. The whole document purports to be from the apostles, but this imposture is not taken seriously by any scholar today. Nevertheless, the work is useful as evidence for the opinions of a part of the Syrian churches towards the end of the fourth century. The list of canonical books was probably added about the year 380. On the omission of Revelation see Cyril of Jerusalem above. See English text.

Peshitta Version. The old Syriac version did not include the four disputed books indicated on the table. These were not generally received as Scripture in the Syrian churches until the ninth century.

Report of Junilius. An African bishop of the sixth century. After visiting the Syrian churches he wrote a work describing their practices, in which his list is given. See Latin text in Westcott, appendix D.

Sub-Apostolic Literature

For a brief survey of works of this class and their place in the early Church, see Metzger, ch. 7

The Shepherd of Hermas. A autobiographical tale about a certain Hermas who is visited by an angelic Pastor (Shepherd), who imparts some legalistic teaching to him in the form of an allegory. Written probably in Rome around A.D. 100.

The Apocalypse of Peter. This work expands upon the Olivet discourse (Mat. 24-25) with descriptions of the last judgment and vivid scenes of heaven and hell. Written about A.D. 130.

The Epistle of Barnabas. A legalistic but anti-Jewish discourse on Christian life falsely ascribed to Barnabas, the missionary companion of Paul. Written probably about A.D. 120 in Italy.

The Epistle of Clement. A letter written about A.D. 100 to the church in Corinth from the church in Rome, and traditionally ascribed to Clement of Rome. The author has heard that the disorderly Corinthians have now ousted their elders, and in this letter he urges them to repent of the action.

Fragments Vrejected Scriptures Meaning

Fragments Vrejected Scriptures Study

| Bible Research >Canon > Disputed NT Books |